Sands Casino Iran

The Las Vegas Sands Corporation, owners of the Sands, Venetian, and Palazzo hotels and casinos, managed to keep details of the scale of the attack under wraps until late last year when it was first suggested that hacktivists in Iran might have been responsible. The $14 billion casino operation came to a standstill and nobody knew what was going on. 25,000 employees of the Sands were completely disconnected and called up the 5-person IT department for help, but they were busy running around the casino, pulling cords out of computers to save whatever they could from what they knew was an attack.

Government accuses Iran of hacking the Las Vegas Sands Casino Corporation, which owns The Palazzo and several other resort-hotel-casinos around the world. At the time, it sounded like just. The nation also destroyed sensitive data during a hack at the Sands Casino in 2014 after anti-Iran comments by owner Sheldon Adelson. Disable Iran's gas and oil sector if Iran hit back too.

Most gamblers were still asleep, and the gondoliers had yet to pole their way down the ersatz canal in front of the Venetian casino on the Las Vegas Strip. But early on the chilly morning of Feb. 10, just above the casino floor, the offices of the world’s largest gaming company were gripped by chaos. Computers were flatlining, e-mail was down, most phones didn’t work, and several of the technology systems that help run the $14 billion operation had sputtered to a halt.

Computer engineers at Las Vegas Sands Corp. (LVS) raced to figure out what was happening. Within an hour, they had a diagnosis: Sands was under a withering cyber attack. PCs and servers were shutting down in a cascading IT catastrophe, with many of their hard drives wiped clean. The company’s technical staff had never seen anything like it.

“This isn’t the kind of business you can get into in Iran without the government knowing”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19584814/1192347541.jpg.jpg)

The people who make the company work, from accountants to marketing managers, were staring at blank screens. “Hundreds of people were calling IT to tell them their computers weren’t working,” says James Pfeiffer, who worked in Sands’ risk-management department in Las Vegas at the time. Most people, he recalls, switched over to their cell phones and personal e-mail accounts to communicate with co-workers. Numerous systems were felled, including those that run the loyalty rewards plans for Sands customers; programs that monitor the performance and payout of slot machines and table games at Sands’ U.S. casinos; and a multimillion-dollar storage system.

In an effort to save as many machines as they could, IT staffers scrambled across the casino floors of Sands’ Vegas properties—the Venetian and its sister hotel, the Palazzo—ripping network cords out of every functioning computer they could find, including PCs used by pit bosses to track gamblers and kiosks where slots players cash in their tickets.

This was no Ocean’s Eleven. The hackers were not trying to empty a vault of cash, nor were they after customer credit card data, as in recent attacks on Target (TGT), Neiman Marcus, and Home Depot (HD). This was personal. The perpetrators wanted to punish the company, or, more precisely, its chief executive officer and majority owner, the billionaire Sheldon Adelson. Although confirming their conjectures would take some time, executives suspected almost immediately the assault was coming from Iran.

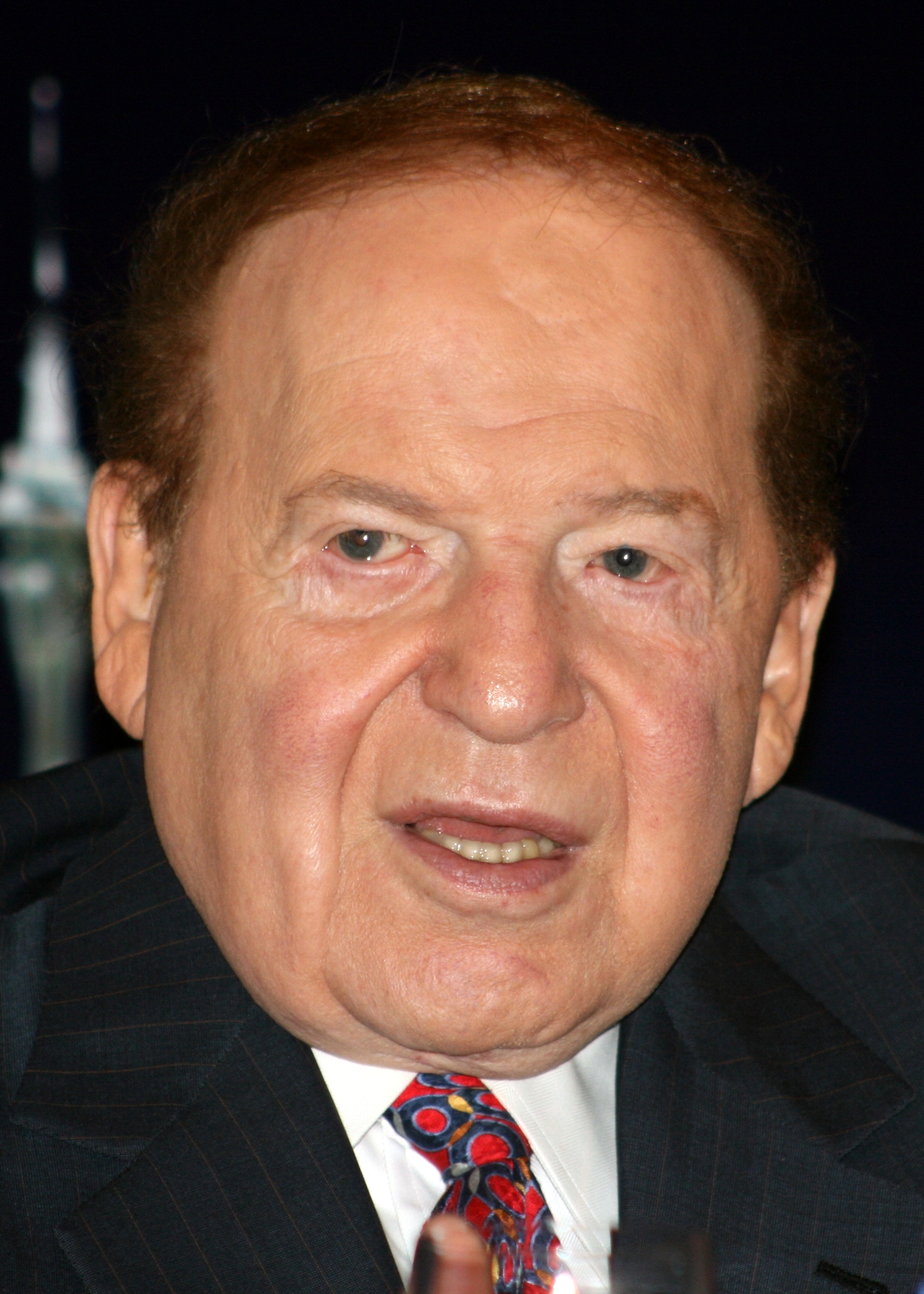

This was new. Other countries have spied on American companies, and they have stolen from them, but this is likely the first time—occurring months before the late November attack on Sony Pictures Entertainment (SNE)—that a foreign player simply sought to destroy American corporate infrastructure on such a scale. Both hacks may represent the beginning of a geopolitically confusing, and potentially devastating, phase of digital conflict. Experts worry that America’s rivals may have found the sweet spot of cyberwar—strikes that are serious enough to wound American companies but below the threshold that would trigger a forceful government response. More remarkable still, Sands has managed to keep the full extent of the hack secret for 10 months. In October 2013, Adelson, one of Israel’s most hawkish supporters in the U.S., arrived on Yeshiva University’s Manhattan campus for a panel titled “Will Jews Exist?” Among the speakers that night were a famous rabbi and a columnist from the Wall Street Journal, but the real draw for the crowd in the smallish auditorium was Adelson, a slightly slumped 81-year-old man with pallid jowls and thinning hair who had to be helped onto the stage by assistants. With a net worth of $27.4 billion, Adelson is the 22nd-wealthiest person in the world, thanks mostly to his 52 percent stake in Las Vegas Sands. He has built the most lucrative gaming empire on earth by launching casinos in Singapore and China whose profits now dwarf those coming from Las Vegas. An owner of three news outlets in Israel and a friend of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Adelson also spends large sums of money to support conservative politicians in the U.S.; he may be best known for contributing some $100 million in a failed attempt to unseat President Obama and elect Republicans to Congress in the 2012 election.

At Yeshiva he described how he’d handle talks with Iran about its ongoing nuclear program. “What are we going to negotiate about?” Adelson asked. “What I would say is, ‘Listen. You see that desert out there? I want to show you something.’ ” He would detonate an American warhead in the sand, he said, where it “doesn’t hurt a soul. Maybe a couple of rattlesnakes and scorpions or whatever.” The message: The next mushroom cloud would rise over Tehran unless the government scrapped any plans to create its own nukes. “You want to be wiped out? Go ahead and take a tough position,” Adelson said, to light applause. It took only a few hours for his remarks to be posted on YouTube (GOOG) and ricochet around the Internet. Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei responded two weeks later, according to the country’s semiofficial Fars News Agency, saying America “should slap these prating people in the mouth and crush their mouths.”

Sands Casino Transbridge

Physically, Adelson and Sands are well protected. He appears in public with a phalanx of armed bodyguards, said to be former agents of the U.S. Secret Service and Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agency. Sands paid almost $3.3 million to protect Adelson and his family last year, according to a company filing. That’s on top of what Sands spends on vaults, security cameras, biometric screening devices, and one of the largest private police forces of any U.S. company, all to safeguard the millions of dollars of cash and chips that flow through its operations every day.

But the company has been slow to adapt to digital threats. Two years ago it had a cybersecurity staff of five people protecting 25,000 computers, according to a former executive. The board authorized a major upgrade of tools and personnel in 2013, but the project was slated to be rolled out over 18 months, and it was in its infancy as Adelson mused about nuclear strikes at Yeshiva. Unbeknownst to Sands, one month after Khamenei’s fiery speech, hackers began to poke around the perimeter of its computer networks, looking for weaknesses. Only later, after the attack, were investigators able to sift through computer logs and reconstruct their movements. These details appear in internal documents describing “Yellowstone 1,” the company’s code name for the incident, and have been corroborated in interviews with a half-dozen people familiar with the breach and its aftermath. Ron Reese, a spokesman for Sands, declined to answer specific questions about the attack or to make Adelson available.

By Jan. 8, 2014, the hackers were focused on Sands Bethlehem, a 3,000-slot-machine casino and resort in Bethlehem, Pa., which has its own website and computer network. It’s a minor outpost in the company’s empire, but going after the weak link in the security chain is a well-worn hacker trick. That day, the hackers launched a first, hourlong attack to try to break into the Sands Bethlehem virtual private network, or VPN, which gives employees access to their files from home or on the road.

The hackers used software that cracks password logins by systematically trying as many as several thousand letter combinations per minute; the software keeps going until it either guesses right or runs out of permutations. It’s a brute-force method, sort of like the safecracking tools in movies that spin through every possible combination to find the correct set of numbers.

The hackers redoubled their efforts on Jan. 21 and 26, again throwing hourslong attacks at the Bethlehem Sands network. Later, investigators would detect the work of at least two different hackers or teams trying different ways to get in. At the time, IT managers in Bethlehem, alarmed at the sudden surge in failed login attempts, began a conference call with Sands security managers in Las Vegas. But brute-force attempts are common—almost half of all companies experience them, according to Alert Logic, a Houston security firm—and the casino staff wasn’t overly concerned. They put another layer of security on the accounts that were being attacked, so that entering the network would require more than just a password.

It was of little use: Five days later, on Feb. 1, the hackers found a weakness in a Web development server used by Sands Bethlehem to review and test Web pages before they went live. Once inside, the pace of the attack quickly escalated. Hackers used a tool called Mimikatz to reveal passwords used previously to log in to a computer or server. Collecting passwords as they went, the hackers gained access to almost every Sands file in Bethlehem, according to three people familiar with the incident. But the Bethlehem computer system was a box—and what they were really after was the key that would let them out.

Sometime before Feb. 9, they found it: the login credentials of a senior computer systems engineer who normally worked at company headquarters but whose password had been used in Bethlehem during a recent trip. Those credentials got the hackers into the gaming company’s servers in Las Vegas. As they rifled through the master network, the attackers readied a malware bomb. Typing from a Sony (SNE) VAIO computer, they compiled a small piece of code, only about 150 lines long, in the Visual Basic programming language. The program proved potent. Not only does it wipe the data stored on computers and servers, but it also automatically reboots them, a clever trick that exposes data that’s untouchable while a machine is still running. Even worse, the script writes over the erased hard drives with a random pattern of ones and zeros, making data so difficult to recover that it is more cost-effective to buy new machines and toss the hacked ones in the trash. Investigators from Dell SecureWorks working for Sands have concluded that the February attack was likely the work of “hacktivists” based in Iran, according to documents obtained by Bloomberg Businessweek. The security team couldn’t determine if Iran’s government played a role, but it’s unlikely that any hackers inside the country could pull off an attack of that scope without its knowledge, given the close scrutiny of Internet use within its borders. “This isn’t the kind of business you can get into in Iran without the government knowing,” says James Lewis, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. Hamid Babaei, a spokesman for Iran’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations, didn’t return several phone calls and e-mails.

Sands Casino Reno Nv

The perpetrators released their malware early in the morning on Monday, Feb. 10. It spread through the company’s networks, laying waste to thousands of servers, desktop PCs, and laptops. By the afternoon, Sands security staffers noticed logs showing that the hackers had been compressing batches of sensitive files. This meant that they may have downloaded—or were preparing to download—vast numbers of private documents, from credit checks on high-roller customers to detailed diagrams and inventories of global computer systems. Michael Leven, the president of Sands, decided to sever the company entirely from the Internet.

It was a drastic step in an age when most business functions, from hotel reservations to procurement, are handled online. But Sands was able to keep many core operations functioning—the hackers weren’t able to access an IBM (IBM) mainframe that’s key to running certain parts of the business. Hotel guests could still swipe their keycards to get into their rooms. Elevators ran. Gamblers could still drop coins into slot machines or place bets at blackjack tables. Customers strolling the casino floors or watching the gondolas glide by on the canal in front of the Venetian had no idea anything was amiss.

Photograph by Paul Hilton/EPA/CorbisAdelson at the Venetian Macau

Leven’s team quickly realized that they’d caught a major break. The Iranians had made a mistake. Among the first targets of the wiper software were the company’s Active Directory servers, which help manage network security and create a trusted link to systems abroad. If the hackers had waited before attacking these machines, the malware would have made it to Sands’ extensive properties in Singapore and China. Instead, the damage was confined to the U.S.

The next day, the hackers took aim at the company’s websites, which were hosted by a third party and still running. The hackers defaced them, posting a photograph of Adelson chumming around with Netanyahu, as well as images of flames on a map of Sands’ U.S. casinos. At one point, they posted an admonition: “Encouraging the use of Weapons of Mass Destruction, UNDER ANY CONDITION, is a Crime,” signing it “Anti WMD Team.” The hackers left messages for Adelson himself. One read, “Damn A, Don’t let your tongue cut your throat.” They also included a scrolling list of information about Sands Bethlehem employees that had been stolen in the breach, including names, titles, Social Security numbers, and e-mail addresses.

/posttv-thumbnails-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/01-03-2020/t_f5acb2b7a1a04887972e5f9ed3df855e_name_thumb_iran_00000.jpg)

In the days after the hack, Sands initially told the press only that its websites had been vandalized and that some office productivity systems, including e-mail, weren’t working. Apparently angered that their attack was being minimized, the hackers took to YouTube, posting an 11-minute video set to the music of Carl Orff’s pulsing cantata O Fortuna. It began by scrolling through a news article that highlighted Adelson’s comments about nuking Iran. Then it showed a computer screen packed with thousands of files and folders, with names such as IT Passwords and Casino Credit, which had been pilfered from Sands.

In the video, which was removed within hours by law enforcement, an unseen hacker clicks into a disk drive titled “Damn A” and enters a folder containing almost a terabyte of data. A text box appears: “Do you really think that only your mail server has been taken down?!! Like hell it has!!” Three people familiar with the Sands hack confirmed the files seen in the video were genuine.

The company is still tallying the damage. Documents and interviews with people involved in Yellowstone 1 show that the hackers’ malicious payload wiped out about three-quarters of the company’s Las Vegas computer servers. Leven, in a brief interview last month before a private event, estimated that recovering data and building new systems could cost the company $40 million or more. For years, U.S. officials have warned of the threat of destructive digital attacks against American companies by foreign parties. The latest alarm came on Nov. 20, from National Security Agency Director Michael Rogers, as he testified before the House Intelligence Committee. Pointing to a 2012 attack on Saudi Aramco that wiped out 30,000 of the oil company’s computers, Rogers suggested that corporate America so far has been lucky. He kept mum about Sands, even though the attack has been studied and discussed by U.S. national security officials since February.

Months after the Sands fiasco, and just days after Rogers’s comments, hackers broke into Sony Pictures Entertainment, crippling the studio’s e-mail, payroll, and other systems and leaking gigabytes of company secrets, including full-length cuts of five major holiday films and the Social Security numbers of 47,000 employees and contractors, including Sylvester Stallone and Judd Apatow. Sony hasn’t publicly said who’s responsible, but according to two people familiar with the incident, FireEye security experts the company hired have connected the attack to a group of hackers known as DarkSeoul, which South Korean and U.S. officials believe works for the North Korean government. The regime denies responsibility, but in June, after learning of the Sony project The Interview—a comedy about an assassination plot against leader Kim Jong Un—a government spokesman said North Korea would “mercilessly destroy anyone who dares hurt or attack the supreme leadership of the country, even a bit.”

This is the next frontier of cyberwarfare. If an enemy of the U.S. were to digitally target the country’s electrical grid or natural gas pipelines, the president would consider a range of powerful responses, including military options, according to leaked descriptions of two executive orders signed by President Obama. But Las Vegas casinos don’t deliver essential services to the U.S. population, apart from Cirque du Soleil addicts. Nor do movie studios. Even months of nuisance attacks on the websites of major American banks in 2012 and 2013, which U.S. intelligence officials connected to Iran’s Republican Guard, didn’t meet the threshold. The damage wasn’t serious enough.

“If this would have come across my desk when I was in government, I would have just put it in the outbox,” Michael Hayden, former director of both the CIA and the NSA, says of the Sands attack. The U.S. government will help find who did it, but it won’t hit back. That leaves most companies pretty much on their own to face a growing cast of global antagonists wielding devastating digital weapons, he says. “If there is a physical Chinese attack coming up the Houston Ship Channel, I know who to call,” Hayden says. “If there is a cyber Chinese attack coming up the fiber-optic cable in the Houston Ship Channel, what does U.S. law say the U.S. government should do? I think what we’re finding is there isn’t a real robust answer.”

“Do you really think that only your mail server has been taken down?!! Like hell it has!!”

As early as 2008, military planners were at work on a series of briefing papers about deterrence in cyberspace, examining whether the same principles that kept the Cold War cold could be applied to the coming generation of digital conflict. The answer, they concluded, was no. It’s a lot easier to tell who fired a nuclear weapon than a digital one, which is simple to acquire and hard to trace. States often outsource hacking to proxies, including groups that behave a lot like the ones that officially took credit for both Sands (the “Anti WMD Team”) and Sony (the “Guardians of Peace”).

In the Sony hack, the first big upload of stolen data was made from Thailand, using the Wi-Fi network of the St. Regis Bangkok, a luxury hotel. Internet functionality in North Korea is so limited that hackers working for the country’s military have set up satellite offices in China, Syria, and other countries. But the attackers could also be hired guns. While denying involvement in the hack, a spokesman for the National Defense Commission in Pyongyang praised it as a “righteous deed.” The spokesman suggested the perpetrators might have been upset over The Interview, “a film abetting a terrorist act while hurting the dignity of the supreme leadership.” FireEye investigators initially prepared a blog post linking DarkSeoul to the attack, but during a meeting on Dec. 3, Sony’s general counsel squelched it, perhaps unwilling to poke the hornet’s nest again. A Sony spokesman said the company’s investigation is ongoing. Similarly, Dell SecureWorks submitted an incident brief to Sands stating that the “attack was in response to CEO comments regarding Iran.” Sands executives made their displeasure known, and the next internal report from Dell, about a month later, omitted that page. Dell spokeswoman Elizabeth Clarke declined to comment.

Courtesy Las Vegas Sands CorporationThe Venetian, on the Strip

A growing number of experts, including former national security officials who’ve seen the problem from the inside, say the next escalation may be companies doing what the U.S. government won’t. If states can hire hackers to do damage, why can’t their victims defend themselves using the same techniques? The topic, discussed often at panels and conferences, is among the options U.S. officials have considered—and rejected—as a response to growing cyberthreats against companies. Hayden, the former NSA director, calls it the digital equivalent of the “stand your ground” laws that allow citizens of some states to defend themselves with lethal force. To critics, it’s a path to a digital Wild West.

Federal law would have to be changed first, and the Department of Justice has signaled that companies trying to “hack back” would be subject to criminal penalties under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, among other statutes. Nations that are already a headache for Obama and his national security team seem to understand this and are turning to low-level digital skirmishing to wreak havoc in the computers of American companies.

Sands Casino Reno Buffet

It’s not the cyberwar many predicted, yet it’s devastating in its own way. “Maybe we never get to a digital Pearl Harbor everyone is always talking about, where it all happens at once, and trillions of dollars in value is wiped out,” says Jason Syversen, founder of Siege Technologies, which provides cyberwarfare tools to the U.S. government. “Maybe it’s just going to go like this—death by a thousand cuts.”